Concepts

Bob is, at its core, just another package build system. Conceptually it is divided into two parts: a front end that reads a domain specific language that describes how to build packages, and several backends that can build these packages.

Recipes, Classes and Packages

All build information for Bob is declared in so called recipes. Effectively they are blueprints for what should be built. The mathematical term for Bob’s recipes would be that of a “function”. A package is the result of the function, that is when the recipe was “computed”. To keep things simple, common parts of multiple recipes may be stored in classes.

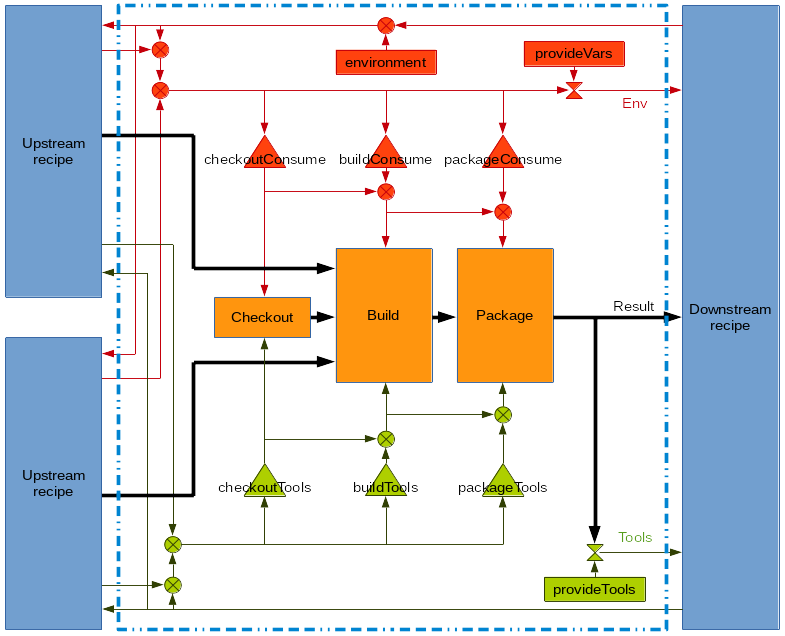

Some parts of the recipe may depend on additional information that is provided by other recipes. The computed result of a recipe, where all inputs are resolved, is called a package. Each package is created from a single recipe but there might be multiple packages that are created from a particular recipe. Inside each recipe there are always three steps: checkout, build and package. The following picture shows the processing inside a recipe and the interaction with downstream and upstream recipes:

There are four kinds of objects that are exchanged between recipes: results,

dependencies, environment variables and tools. Results (shown as black arrows)

are always propagated downstream. These are the actual build artifacts that are

created. Dependencies (upstream recipes) may be propagated downstream which is

not shown in the picture. Environment variables are key-value-pairs of

strings. They are passed as shell variables to the individual build steps.

Tools are scripts or executables that are needed to produce the build result,

e.g. compilers, image generators or post processing scripts. Consuming recipes

of tools get the directory of the required tool added to their $PATH so that

they are available for the build steps. By explicitly defining the dependencies

and required environment variables/tools of a recipe, Bob can track changes that

influence the build result with a high degree of certainty.

The actual processing during build time is done in the orange steps. They are scripts that are executed with (and only with) the declared environment and tools. Bob assumes that the result of the steps depends only on the scripts themselves, their environment and tools. Additionally, Bob assumes that the “build” and “package” steps are deterministic in the sense that they produce equivalent results for the same input. Equivalent results may not necessarily be bit identical but must have the same function and must thus be interchangeable. This property is required to reuse binary build results from previous build runs or from external build servers.

The flow of environment variables is depicted in red while the flow of tools is shown in green. By default only build results and dependencies are exchanged. A recipe may declare that it consumes certain environment variables ({checkout,build,package}Vars) and tools ({checkout,build,package}Tools). On the other hand a recipe may also declare to provide a dependency, tool or variable, providing the necessary input for downstream recipes. If a tool or environment variable is used without declaring its usage, Bob will stop processing. This will either happen when parsing the recipes (if detectable) or during execution of the build. All executed scripts are configured to fail if an undefined variable is used or any command returns a failure status.

Implicit versioning

A key concept of Bob is that recipes do not have an explicit version. Instead, Bob constructs an implicit version that is derived from the recipe and the input to this recipe when building a particular package. This is called the Package-Id. The recipe language is static in the sense that the Package-Id of a package can be calculated in advance without executing any build steps. This enables Bob to determine exactly when a package has to be built from scratch (e.g. the build script changed) or if Bob has to build several packages from the same recipe due to varying input parameters.

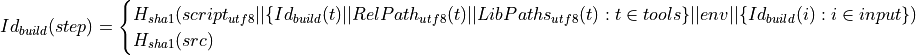

Technically, the Package-Id is the Variant-Id of the package step. The Variant-Id of each step (checkout, build and package) is calculated as follows:

where

script is the script of the step,

tools is the sorted list of tools that are consumed by the step,

env is the sorted list of the environment key-value-pairs and

input is the list of all results that are passed to the step (i.e. previous step, dependencies).

To keep the Variant-Id stable in the long run, the scripts of SCMs in the checkout step are replaced by a symbolic representation.

There exists also a second implicit version, called Build-Id, which identifies the build result in advance. The Build-Id can be used to grab matching build artifacts from another build server instead of building them locally. The Build-Id is derived from the actual sources created by the checkout step, the build/package Scripts, the environment and all Build-Ids of the recipe dependencies:

where

script is the symbolic script of the step,

tools is the sorted list of tools that are consumed by the step,

env is the sorted list of the environment key-value-pairs and

input is the list of all results that are passed to the step (i.e. previous step, dependencies).

src are the actual sources created by the checkout step

The special property of the Build-Id is that it represents the expected result. To calculate it, all involved checkout steps have to be executed and the results of the checkouts have to get hashed.

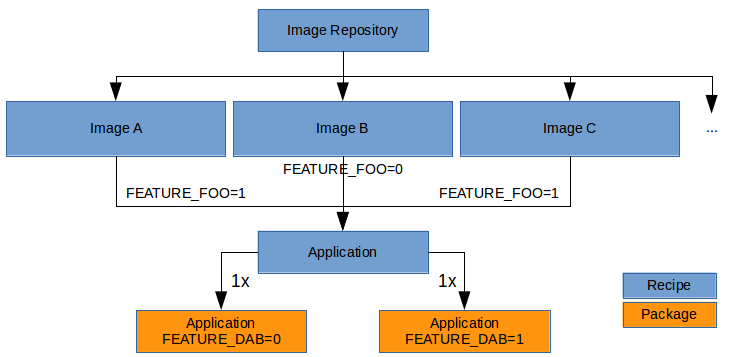

Variant management

Variant management is handled entirely by environment variables that are passed to the recipes. Through implicit versioning, Bob can determine if multiple packages have to be built from the same recipe due to varying environment variables.

Variant management will typically be done by defining a dedicated environment variable for each feature, e.g. FEATURE_FOO which is either disabled (“0”) or enabled (“1”). A recipe declares that it depends on this variable in the build step by listing FEATURE_FOO in the buildVars clause. Through this declaration, Bob can selectively set (only) the needed environment variables in each step and can track their dependency on them. When building the whole software, Bob can calculate how many variants of the recipe have to be built by resolving all dependent variables.

Re-usage of build artifacts

When building packages, Bob will use a separate directory for each Variant-Id. Future executions of a particular step will use the same directory unless the step is changed and gets a new Variant-Id. By using the Variant-Id as discriminator, a safe incremental build is possible. The previous directory will be reused as long as the Variant-Id is stable. If anything is changed that might influence the build result (step itself or any dependency), it will result in a new Variant-Id and Bob will use a new directory. Likewise, if the changes are reverted, the Variant-Id will get the previous value and Bob will restart using the previous directory.

In local builds, the build results are shared directly with downstream packages by passing the path to the downstream steps. On the Jenkins build server the build results are copied between the different work spaces.

Based on the Build-Id, it is possible to fetch build results of a build server from an artifact repository instead of building it locally. To compute the Build-Id, Bob needs to know the result of the checkout step of the recipe (either by having cached the anticipated result of deterministic checkout steps or by running it) and all its dependencies. Then Bob will look up the package result from the artifact repository based on the Build-Id. If the artifact is found it will be downloaded and the build and package steps are skipped. Otherwise the package is built as always. Additionally, Bob requires the following properties from a recipe:

The build and package steps have to be deterministic. Given the same script with the same input it has to produce the same result, functionality-wise. It is not required to be bit-identical, though.

The build result must be relocatable. The build server will very likely have used a different directory than the local build. The result must still work in the local directory.

The build result must not contain references to the build machine or any dependency. Sometimes the build result contains symlinks that might not be valid on other machines.

Under the above assumptions Bob is able to reliably reuse build results from other build servers.

Sandboxing

By utilizing user namespaces on Linux, Bob is able to execute the package steps in a tightly controlled and reproducible environment. This is key to enable binary reproducible builds. The sandbox image itself is also represented by a recipe in the project. This allows to define different sandbox images as required and even build the sandbox image itself by multiple recipes. It provides full control about which packages are built in the sandbox.

Inside the sandbox, the result of the consumed or inherited sandbox image is

used as root file system. Only direct inputs of the executed step are visible.

Everything except the working directory and /tmp is mounted read only to

restrict side effects. The only component used from the host is the Linux

kernel and indirectly Python because Bob is written in this language.

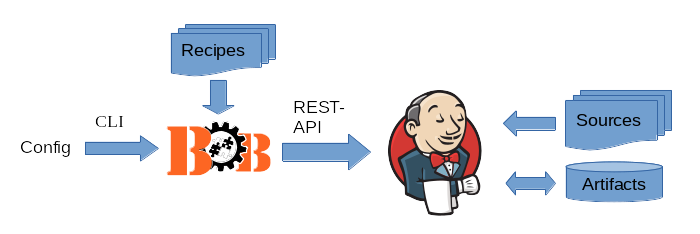

Jenkins support

Bob natively supports building projects on Jenkins servers through the bob-jenkins command. In contrast to local builds, the recipes do not need to be present on the Jenkins server. Instead, Bob configures the Jenkins server based on a project and some user settings by creating the jobs through the REST-API and storing all required information in the jobs themselves.

Principle operation

For each project the user creates the configuration that consists at least of the Jenkins server URL and the packages that shall be built. Bob then configures the Jenkins through its REST-API, creating and updating the Jobs required to build the project.

By default Bob will create one job per recipe. If required, multiple jobs per recipe will be created if the job dependency graph would be cyclic. All jobs can be executed on different build nodes to leverage the performance of a build cluster. As the project evolves, updates to recipes can be regularly synced to the Jenkins server. This will only update the affected jobs.

Bob makes no assumption about how many build nodes are used and where the jobs are built as long as the build nodes are identical. The chosen nodes can be controlled with standard Jenkins node expressions.

Natively supported SCMs

For git and Subversion repositories Bob will use the respective plugins that are available on Jenkins. This enables to trigger builds of jobs where the source code was changed. Either this is done by polling the SCM server or by installing commit hooks that inform the Jenkins server about potential changes.

The principle mode of operation is the same for all natively supported SCMs on Jenkins:

Bob configures the job to use the git/svn plugin to checkout the sources.

Initial build of the job. Jenkins stores which revision was built.

Some changes are pushed to a branch that was built in this Jenkins project.

Jenkins polls the SCM server. Either by schedule or because a commit hook informed the Jenkins server about the change immediately.

The affected job(s) are built. Once finished, all dependent jobs will be automatically triggered.

Because cvs and url SCMs do not use Jenkins plugins to fetch the sources, there is currently no automatic CI build possible with these SCMs. Such jobs need to be triggered by other means if the sources are changed.

Artifact handling

By default Bob will use the built-in artifact handling of Jenkins. This has the advantage that the build results will be available in each build directly on the Jenkins UI. For larger projects this is not optimal, though, because Jenkins is struggling with large artifacts and if many jobs are built in parallel. To relieve the Jenkins master from handling the artifacts, it is possible to exchange the artifacts exclusively through one or more dedicated artifact servers.

For very large and mostly static packages, e.g. toolchains, there exists a special handling for shared packages. These shared packages are not copied into every job workspace independently but only once onto each Jenkins build node. The installation is done outside of the job workspaces and the jobs will use the package directly from there.

Limitations

The same version of Bob must be used on all build nodes and also on the machine that configured the Jenkins jobs.

All build nodes are assumed to be identical as far as the project is concerned, e.g. the OS or required host tools.

Built packages must be reusable. Most importantly this requires that build result must be relocatable and must not contain references to the build machine or any dependency. E.g. if the build result contains symlinks that point outside of the workspace the result will not be usable on another build node.